Wolkenmilch

a Cloud of Curiosity and Creation

- Introduction

- Breaking the Silence - Emergence of Human Communication

- Ancient Civilizations: The Evolution of Writing and Recordkeeping

- The Pre-Machine Age: 3000 B.C. - 1450 A.D.

- The Abacus: Early Computational Brilliance

- The Power of Smoke: Signaling Danger

- The Phoenician Alphabet: Streamlining Communication

- Greek Innovation: Adding Vowels for Clarity

- Libraries: Centers of Learning and Knowledge Preservation

- Hindu–Arabic Numerals: Revolutionizing Numbers

- Economic Impact of Pre-Machine Age Innovations

- Mechanical Age from 1450 to 1840

- Electromechanical Age (1840 - 1940)

- Electronic Age from 1940 Onwards

- Conclusion

- References

From Cave Paintings to Cyberspace

by

Introduction

Throughout human history, the way we communicate, store, and disseminate information has undergone significant transformations. These shifts are often termed as “information revolutions,” which can be defined as pivotal changes in the methods and mediums used for information exchange. These revolutions fall into two broad categories: systems and mediums. Systems, such as the alphabet or the binary code, serve as frameworks of symbolic representations. On the other hand, mediums like stone, paper or digital storage act as vessels for these symbols.

The interplay between new mediums and systems is intriguing; the advent of one often catalyzes the development of the other. For example, the invention of the printing press led to the widespread use of the Latin alphabet, and the development of the internet gave rise to new coding languages.

Understanding these information revolutions is more than an academic exercise; it serves as a lens to view the broader contours of human progress. These revolutions have had a profound impact on various aspects of civilization, such as governance, trade, culture, and social interactions. They have accelerated scientific advancements, shaped global economies, and even influenced the outcomes of wars.

By studying these shifts, we can gain valuable insights into the changing dynamics of power, the dissemination of knowledge, and the evolving nature of human connectivity. Recognizing and appreciating these changes equips us to better navigate the present and prepare for the future, ensuring that we remain adaptive, resilient, and forward-looking as a civilization.

Breaking the Silence - Emergence of Human Communication

The realm of animal communication, though intricate in its own right, has inherent limitations. Most animal communication methods are instinctual, driven by immediate needs or reactions to the environment. For instance, a specific bird call might indicate the presence of a predator, while a particular dance in bees can pinpoint the location of nectar. These methods, while effective, lack the depth and versatility found in human communication.

Transitioning to early humans, our ancestors not only used vocal sounds but also began to harness body language as a powerful communicative tool. Gestures like handshakes evolved as symbols of trust, facial expressions conveyed a spectrum of emotions, and actions like laughing or crying became universal indicators of joy or distress. These non-verbal cues added layers of complexity to human interactions, allowing for more nuanced communication.

The emergence of speech was a monumental leap in this journey. In early human societies, speech became the primary medium for sharing knowledge, expressing emotions, issuing warnings, and building social bonds. It allowed for the conveyance of abstract ideas, planning for the future, and reflecting on the past—capabilities that were likely beyond the scope of animal communication.

Oral traditions, encompassing storytelling, songs, and chants, played a pivotal role in preserving cultural narratives and historical events. For instance, the Aboriginal Australians used “Dreamtime” stories to explain the origins of the world and pass down important cultural knowledge. Similarly, the epic tales recited by the Griots in West Africa served as both entertainment and historical documentation, preserving centuries of history through song and story. These traditions became the bedrock of cultural preservation, ensuring that the wisdom of one generation was seamlessly passed to the next.

In essence, the birth of language and the rich tapestry of oral traditions were the first major steps in the intricate dance of information transmission that we continue to evolve today.

Cultural Capital in Prehistoric Societies

The emergence of language and oral traditions in prehistoric societies had far-reaching implications for economics, trade, and the concept of money. First and foremost, language acted as a catalyst for trade. It enabled early humans to negotiate, establish value for goods, and create rudimentary contracts, essentially laying the foundation for organized trade systems. This was a monumental leap from simple barter systems, as language allowed for more complex transactions and the establishment of social hierarchies, which are crucial for any economic system.

Oral traditions, on the other hand, served as a unique form of “cultural capital.” These stories, songs, and chants preserved valuable information, from land use and resource allocation to social norms and trade practices. This cultural capital had economic worth, as it could be “traded” through the sharing of knowledge and skills, thereby influencing economic decisions and resource management. In essence, oral traditions acted as an early form of record-keeping, capturing the collective wisdom and practices that would shape economic activities for generations to come.

Together, language and oral traditions were not just tools for communication; they were the bedrock upon which complex economic systems could be built. They facilitated the transition from isolated communities to integrated societies, capable of sophisticated trade and economic planning. These early forms of communication were the stepping stones to the intricate economic systems that have evolved over millennia, shaping the way we think about economics, trade, and money today.

Ancient Civilizations: The Evolution of Writing and Recordkeeping

From Symbols to Scripts

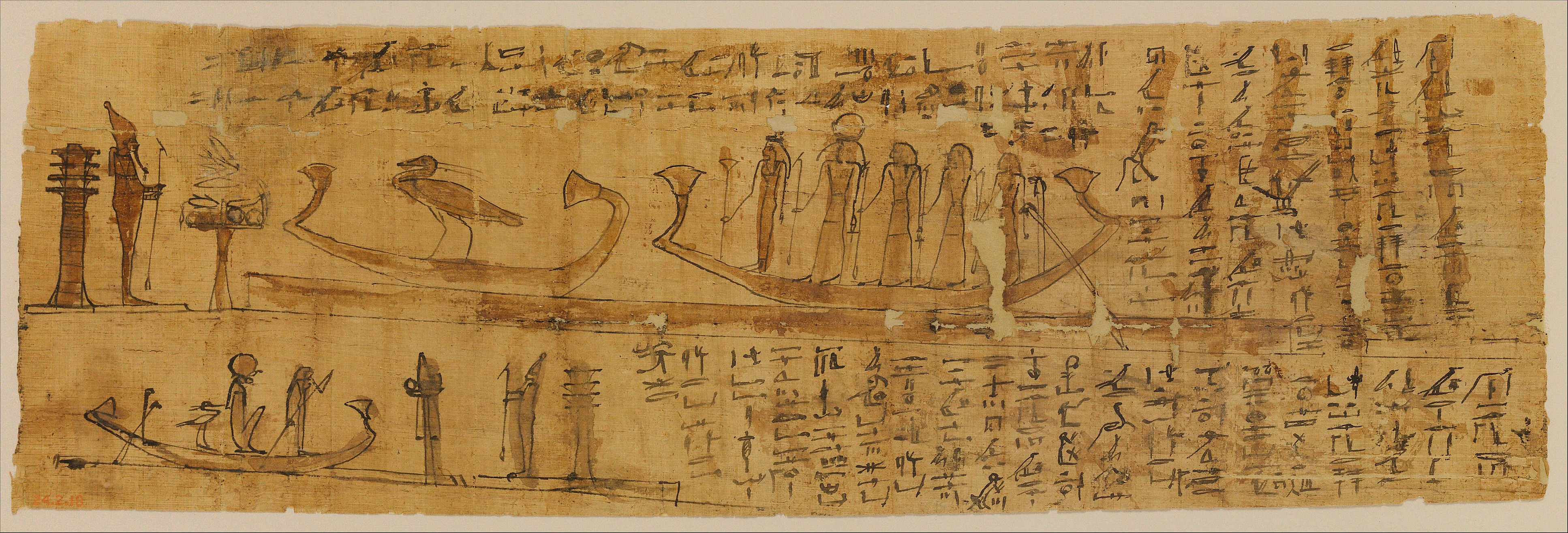

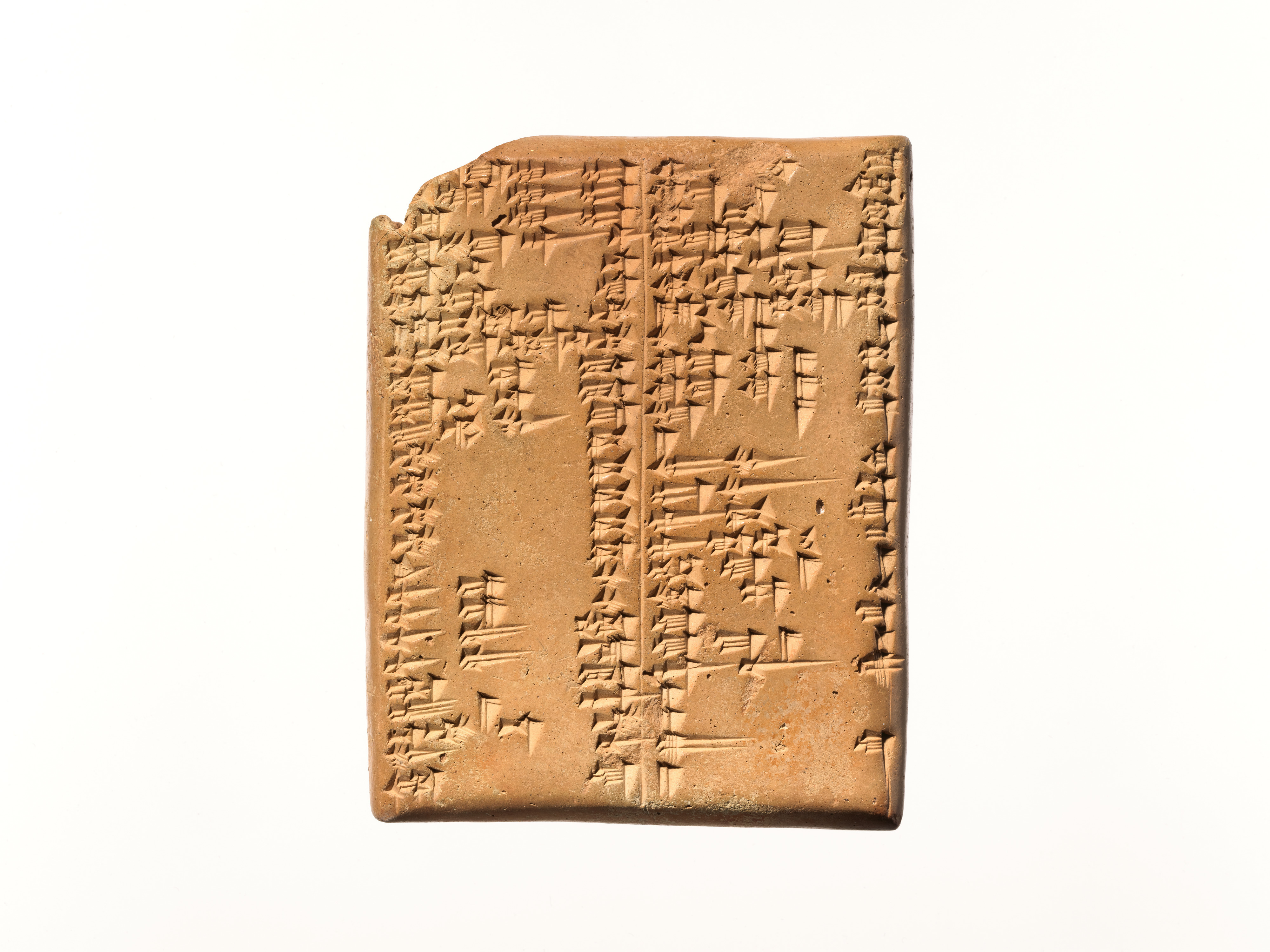

The inception of human expression and documentation can be traced back to rudimentary symbols, such as cave paintings from around 30,000 BC and petroglyphs dating to approximately 10,000 BC. Fast forward to 3500 BC, and the Sumerian city of Kish became the cradle of cuneiform, a script meticulously carved into clay tablets. Nearly concurrently, around 3200 BC, the Egyptians unveiled hieroglyphics, a complex system that originated as pictograms but later matured into an intricate form of picture writing. Far from being mere artistic pursuits, these early scripts were pivotal in governance, commerce, and the archiving of information, thereby establishing the groundwork for organized societies.

Alphabets as Chronicles of History and Myth

The transformation of writing systems has been nothing short of remarkable. It commenced with pictograms, visual symbols that encapsulated entire concepts or objects—akin to the modern symbols we see for “no smoking” or pedestrian crossings. As societies advanced, so did their modes of communication. Logograms or ideograms emerged, symbolizing entire words or specific notions, much like our contemporary symbols for percentages or legal references. However, the true linguistic watershed moment arrived with the introduction of phonograms, which were symbols representing individual sounds. This innovation paved the way for the creation of comprehensive alphabets. In civilizations such as Egypt and Greece, these alphabetic systems seamlessly blended the realms of illustration and script, enabling the chronicling of history, myths, and more.

Writing Mediums - From Stone to Paper

The materials chosen by humans for inscribing their thoughts have also evolved considerably, reflecting the progress of civilizations themselves. Initial inscriptions were etched onto durable but unwieldy substances like stone and clay. However, the advent of papyrus around 3000 BC in Egypt signaled a paradigm shift. This lightweight and versatile material, initially a closely guarded Egyptian secret, soon became a sought-after export. The importance of papyrus as a medium is monumental; it served as the precursor to subsequent materials like leather and linen, and eventually, paper. These substrates not only simplified the task of recording information but also significantly aided its dissemination, playing a crucial role in the transference of knowledge across different regions and generations.

Economics and the Power of Writing

The emergence of writing systems such as cuneiform and hieroglyphics exerted a transformative influence on the economies of ancient civilizations. For instance, cuneiform script in early Mesopotamia was initially employed to document economic activities like trade transactions and tax collections. This systematic approach allowed for a more transparent and organized economic structure, minimizing the risk of fraudulent activities and disputes. In Ancient China, oracle bone inscriptions were utilized for divination, which likely had implications for agricultural planning and thus economic stability. In the Andean region of South America, the use of quipu—knotted strings—served as a unique method for archiving transactions and calculations, thereby facilitating commerce among Andean cultures.

The transition from heavier materials like stone to more manageable mediums such as papyrus also had economic repercussions. The lighter and more versatile nature of papyrus made it more convenient to store and transport records, likely leading to an uptick in long-distance commerce and making recordkeeping more accessible to smaller traders, thereby democratizing economic participation.

The Pre-Machine Age: 3000 B.C. - 1450 A.D.

The pre-machine age, spanning over four millennia, was a testament to human ingenuity and was teeming with innovations that laid the groundwork for future technological advancements. Early civilizations transitioned from rudimentary inscriptions on stone and clay to more sophisticated writing mediums, marking the dawn of organized record-keeping.

The Abacus: Early Computational Brilliance

The abacus, developed between 2700 to 2300 BC, stands as a symbol of early computational brilliance, simplifying arithmetic long before the advent of modern calculators. Its origins can be traced back to ancient civilizations where it began as a simple counting board or table. Over time, its design evolved, and by the time it reached China, it took on the form most are familiar with today: a frame with rods or wires, each strung with movable beads or marbles. These beads represent different numerical values and can be moved to perform arithmetic operations. The abacus’s design made it not only a practical tool for calculations but also a portable one, allowing merchants, scholars, and others to carry it with them and use it wherever they went.

The Power of Smoke: Signaling Danger

By 1800 BC, the art of sending messages through smoke signals emerged, offering a rudimentary yet effective means of long-distance communication. They were used to transmit news, signal danger, or gather people to a common area. The bandwidth of smoke signals is quite limited, with a rate of about 8 characters per minute, equivalent to 0.13 bits per second or 1 byte per minute. This is a stark contrast to modern communication methods, but for ancient civilizations, it was revolutionary. In ancient China, soldiers stationed along the Great Wall utilized smoke signals to warn of enemy invasions. The color of the smoke would indicate the size of the invading party. By placing beacon towers at regular intervals and having a soldier in each tower, messages could be relayed across the entire 7,300 kilometers of the Wall. This system not only warned of invasions but also allowed inner castles to prepare defenses and coordinate troop movements.

The Phoenician Alphabet: Streamlining Communication

The Phoenician alphabet, introduced around 1100 BC, was a groundbreaking development in the annals of human communication. Consisting of 22 consonant characters, it eliminated the need for cumbersome pictographs and ideograms that characterized earlier writing systems. This streamlined form of communication was not only efficient but also versatile, making it easier to learn and adapt. As a result, the Phoenician script laid the foundation for many subsequent alphabets, including Greek, Latin, and even Aramaic, from which the Hebrew and Arabic scripts evolved.

Greek Innovation: Adding Vowels for Clarity

The Greeks, always keen on improving and refining existing knowledge, took the Phoenician system and added a significant innovation: vowels. By introducing vowels around 800 BC, they made their writing more phonetically accurate and expressive. This enhancement allowed for clearer articulation of words and ideas, paving the way for advancements in literature, philosophy, and science.

Libraries: Centers of Learning and Knowledge Preservation

The emphasis on knowledge preservation and dissemination in Greek society led to the establishment of several iconic institutions. Among them was the Tyrant’s library, a testament to the Greek commitment to learning. Libraries like these were not just repositories of scrolls and books; they were centers of intellectual discourse, attracting scholars, poets, and thinkers from various parts of the world. The Tyrant’s library, in particular, was renowned for its vast collection, which encompassed works on diverse subjects from philosophy to astronomy. Such institutions played a pivotal role in shaping the intellectual landscape of the ancient world, ensuring that the wisdom of one generation was passed on to the next.

Hindu–Arabic Numerals: Revolutionizing Numbers

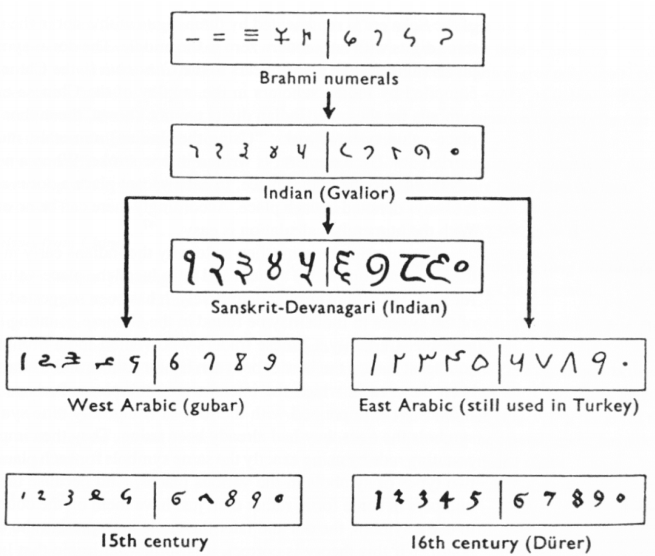

The introduction of the 1-9 digit system, followed by the groundbreaking concept of “zero” by 875 A.D., marked a significant turning point in the realm of numerical representation and computation. This system, known as the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, is a decimal place-value system that employs a zero glyph, as seen in numbers like “205”. Its origins can be traced back to the Indian Brahmi numerals. By the 8th to 9th centuries, the full system had emerged and was first described outside India in Al-Khwarizmi’s “On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals” around 825 A.D.. The numeral system’s spread to the Middle East and then to Europe signifies a profound cultural exchange. The system was mentioned in Syria in 662 AD and was later adopted by the Arabs. The Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi and the Arab Al-Kindi played pivotal roles in disseminating this knowledge in the Middle East. By the end of the 7th century, decimal numbers began to appear in inscriptions in Southeast Asia as well as in India.

Economic Impact of Pre-Machine Age Innovations

The pre-machine age was a period of remarkable innovations that had far-reaching economic and trade implications. One of the most significant inventions was the abacus, developed between 2700 to 2300 BC. This early computational tool simplified arithmetic and became indispensable for merchants, facilitating more accurate and quicker transactions. Its portability also meant that traders could easily carry it with them, making it a vital tool for long-distance trade.

Smoke signals, another innovation from this era, were used for long-distance communication. In ancient China, soldiers along the Great Wall used smoke signals to warn of enemy invasions. This early warning system allowed for better preparation and coordination of defenses, indirectly contributing to the stability needed for economic activities like trade.

The Phoenician alphabet, introduced around 1100 BC, streamlined communication by replacing cumbersome pictographs and ideograms. This made recordkeeping more efficient, which was crucial for trade and taxation. The Greeks further refined this system by adding vowels, making their writing more expressive and accurate, which likely had implications for legal documents and contracts, thereby affecting trade and governance.

The establishment of libraries, like the Tyrant’s library in ancient Greece, became centers for intellectual discourse and knowledge preservation. These institutions likely played a role in the dissemination of economic theories and trade strategies, influencing economic policies and practices.

Lastly, the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system around 875 A.D. revolutionized numerical representation and computation. This system made calculations more straightforward and was quickly adopted across various civilizations, facilitating more complex economic models and trade equations.

In summary, the innovations of the pre-machine age laid the groundwork for more complex economic systems and trade networks. They introduced computational tools, improved communication for trade and defense, streamlined recordkeeping, and enhanced numerical systems, all of which had a lasting impact on economics and trade.

Mechanical Age from 1450 to 1840

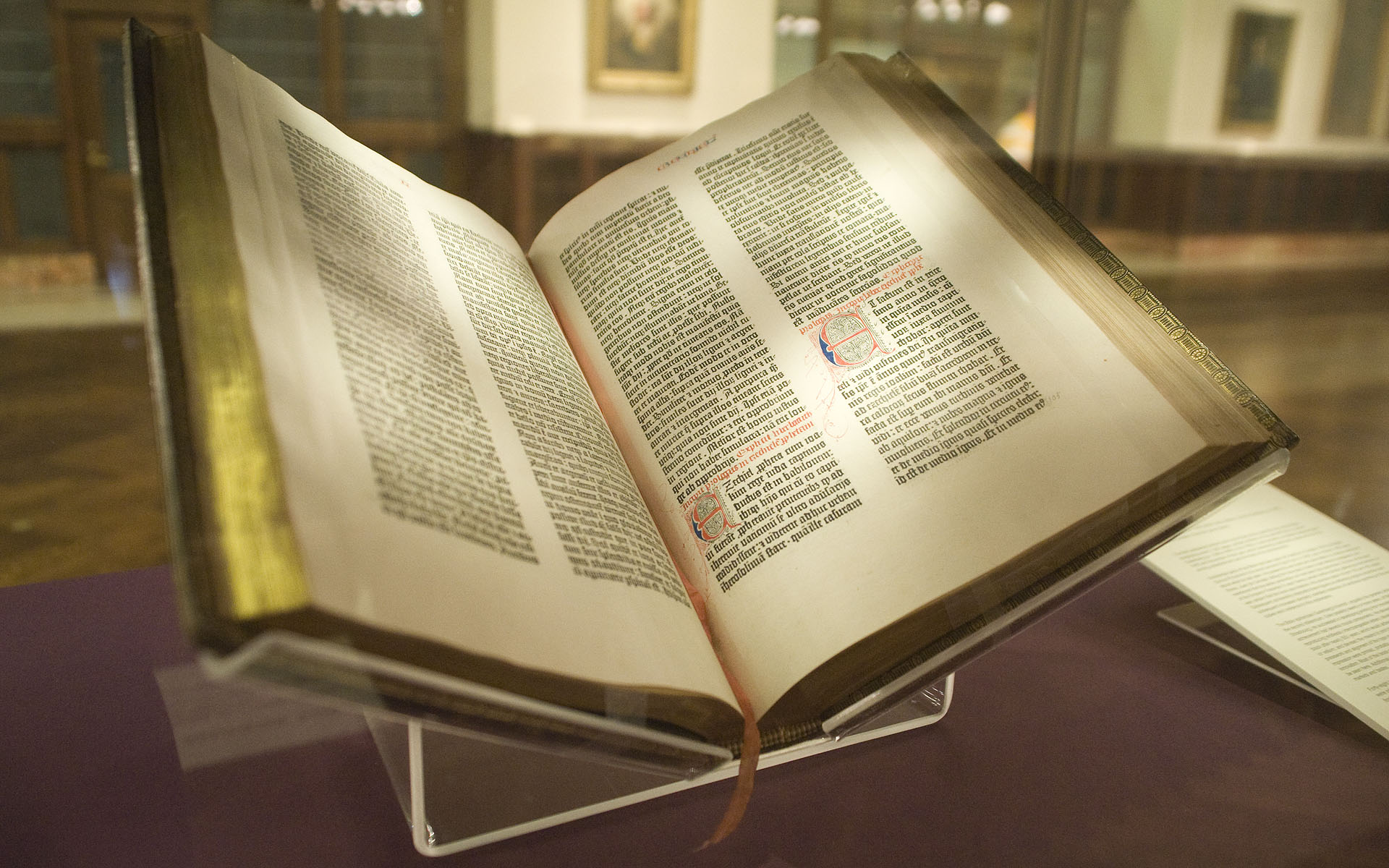

Unleashing the Printing Press: A Knowledge Tsunami

The invention of printing is often associated with Johannes Gutenberg’s press in the 15th century, but the origins of this revolutionary technology trace back to East Asia, particularly China. Printing in East Asia originated during the Han dynasty (220 BCE – 206 CE), evolving from ink rubbings made on paper or cloth from texts on stone tables. One of the most significant advancements in this domain was the development of mechanical woodblock printing on paper, which began in China during the Tang dynasty before the 8th century CE.

However, the Chinese writing system, with its thousands of unique characters, posed challenges for the development of a movable type system. Despite these challenges, the Chinese artisan Bi Sheng invented an early form of movable type using clay and wood pieces arranged for written Chinese characters around 1040 AD. This invention was significant, but its potential was somewhat limited due to the vast number of Chinese characters.

In contrast, the Gutenberg press, with its movable metal type, was particularly suited for the relatively small Latin alphabet, making mass production of texts more feasible. This difference in writing systems partially explains why the Gutenberg press had such a transformative impact in Europe, while earlier Chinese printing innovations, though remarkable, did not lead to the same widespread revolution in information dissemination.

Gutenberg’s Innovations:

Gutenberg’s press was modeled on the design of existing screw presses, and a single Renaissance movable-type printing press could produce up to 3,600 pages per workday, compared to the mere forty by hand-printing. Gutenberg, a goldsmith by profession, introduced two major innovations that drastically reduced the cost of printing books and other documents in Europe:

- Hand Mould: This allowed the precise and rapid creation of metal movable type in large quantities.

- Movable-Type Printing Press: This press was based on the design of existing screw presses, but Gutenberg adapted it to ensure that the pressing power exerted on the paper was applied both evenly and with the required sudden elasticity.

Impact on Knowledge Dissemination: The printing press’s introduction in Europe heralded the era of mass communication. This unrestricted circulation of information transcended borders, empowering the masses during the Reformation and challenging the power of political and religious authorities. The sharp increase in literacy broke the monopoly of the literate elite on education, bolstering the emerging middle class.

Influence on Education, Science, and Religion:

- Democratization of Information: The printing press democratized the creation and dissemination of information, freeing it from the control of authorities, especially the church.

- Enlightenment: The 18th-century Enlightenment was fueled by the spread of ideas through printed materials.

- Religious Reformation: The press played a crucial role in the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther’s theses in 1517, which were widely disseminated due to the printing press, challenged the Catholic Church’s practices and doctrines.

- Scientific Advancements: The rapid spread of scientific ideas and discoveries became possible, leading to more collaborative and swift advancements in various fields.

Notable Printed Materials:

- Bible: The first significant book printed using the press was the Bible, making it accessible to a larger audience.

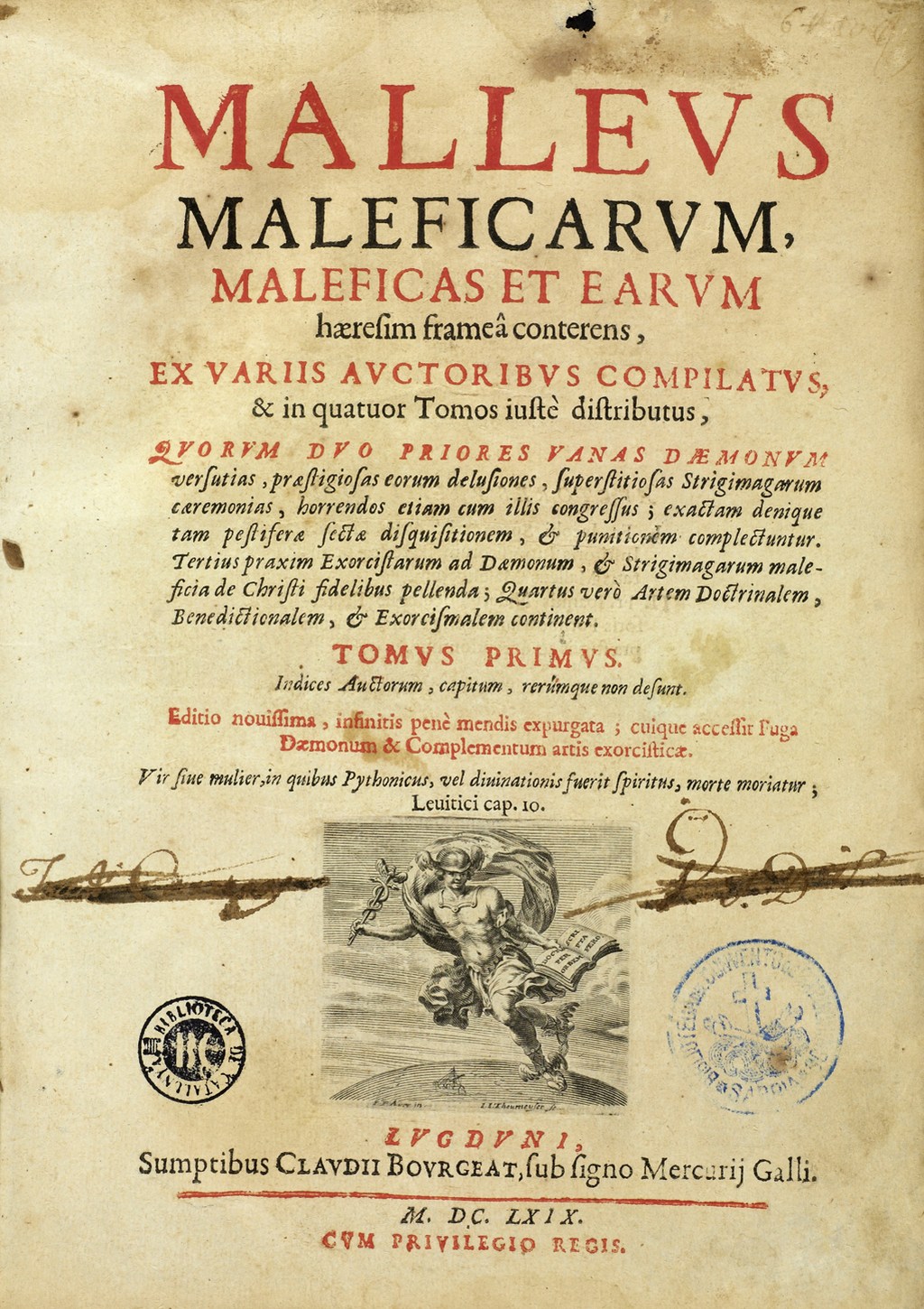

- Hexenhammer (Witch-hammer): Books on witches, like the Hexenhammer, became widespread, influencing societal beliefs and practices.

- Pamphlets: By the 15th century, pamphlets became a popular medium to spread ideas and news.

- Newspapers: The first daily newspaper, “Einkommende Zeitung,” was introduced in Leipzig in 1650, marking the beginning of regular news dissemination.

In essence, the Gutenberg printing press not only revolutionized the way information was shared but also played a pivotal role in shaping societal structures, beliefs, and practices during the Renaissance era.

The Renaissance: Birthplace of Brilliance

The Renaissance, spanning roughly from the 14th to the 17th century, was a vibrant period that witnessed a profound rebirth of art, science, and literature. Originating in Italy and spreading throughout Europe, this era was characterized by a renewed interest in the classical knowledge and principles of ancient Greece and Rome.

Flourishing of Art, Science, and Literature:

-

Art: The Renaissance produced some of the most iconic artworks in history. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael created masterpieces that are celebrated to this day. Techniques such as linear perspective and chiaroscuro (the treatment of light and shadow) were refined, giving paintings a more three-dimensional and realistic appearance.

-

Science: This period also saw significant advancements in the field of science. Figures like Galileo Galilei and Nicolaus Copernicus challenged traditional views of the universe, laying the groundwork for modern astronomy and physics.

-

Literature: Literature flourished with the works of writers like Dante Alighieri, Geoffrey Chaucer, and Erasmus. Their writings, often in the vernacular, made literature more accessible to the general populace.

Role of the Printing Press:

The invention of the Gutenberg printing press in the mid-15th century played a transformative role during the Renaissance. Before its invention, books were painstakingly hand-copied, making them rare and expensive. The printing press democratized access to knowledge by making books more affordable and widely available. This had several implications:

-

Spread of Ideas: The rapid dissemination of ideas became possible. Philosophical and scientific works, previously confined to monastic libraries or the homes of the elite, were now accessible to a broader audience.

-

Education: With the availability of more books, education became more widespread. Universities saw an influx of students eager to learn, and the literacy rate began to rise.

-

Challenging Authority: The printing press facilitated the spread of new and sometimes controversial ideas, challenging the established norms and authorities, especially the church.

In essence, the Renaissance was a period of intellectual and artistic revival, and the printing press played a central role in this awakening. By making knowledge accessible, it empowered individuals, fostered creativity, and paved the way for the modern world.

Evolution of Mechanical Computation

The history of mechanical computing devices dates back thousands of years, with the earliest aids to computation being purely mechanical devices. These devices required the operator to set up the initial values of an arithmetic operation and then manipulate the device to obtain the result. Over time, these devices evolved in complexity and capability.

Slide Rule (1600): The slide rule, invented in the 1620s, was a significant advancement in mechanical computation. It allowed for multiplication and division operations to be carried out much faster than was previously possible. The slide rule was based on logarithmic scales and was a crucial tool for engineers and other professionals for centuries.

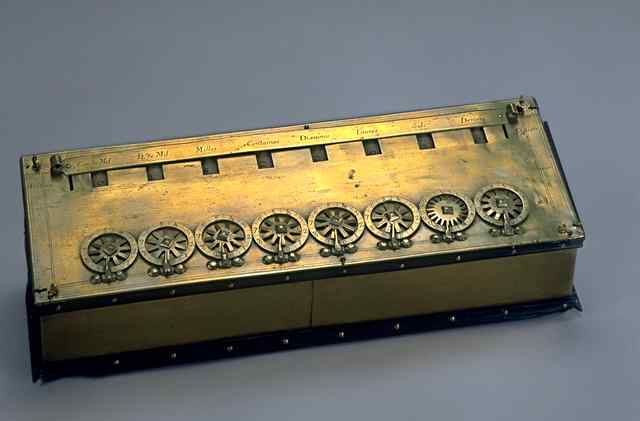

Pascaline (1642): Blaise Pascal, a French mathematician and physicist, invented the Pascaline in 1642. This mechanical calculator was capable of addition and subtraction. Pascal’s invention was groundbreaking, and he built several of these machines over the next decade. The Pascaline laid the foundation for future mechanical calculators and showcased the potential of mechanized computation.

Difference Machine (1820): The Difference Machine, conceptualized by Charles Babbage in 1820, was designed to compute polynomial functions. Although Babbage’s design was never fully realized in his lifetime, the concept of the Difference Machine was revolutionary. It was intended to produce mathematical tables, which were crucial for navigation and other scientific endeavors.

Limitations and Implications: While these mechanical devices were groundbreaking, they had their limitations. For instance, the Difference Machine could only perform one type of calculation at a time. However, these machines played a pivotal role in various sectors:

- Trade: Mechanical calculators like the Pascaline made it easier for merchants to perform quick calculations, streamlining trade and commerce.

- Scientific Endeavors: Devices like the slide rule and the Difference Machine were invaluable to scientists, engineers, and navigators. They facilitated complex calculations that would have been time-consuming and prone to error if done manually.

- Education: These devices also found their way into educational institutions, helping students understand mathematical concepts better and fostering an interest in computation.

In conclusion, the development of mechanical computing devices marked a significant step forward in the history of computation. They not only simplified complex calculations but also paved the way for the modern computers we use today.

Predecessors to Binary: Ancient Systems from Around the World

The binary system, often referred to as the base-2 numeral system, is a method of mathematical expression that uses only two symbols: “0” and “1”. This system is foundational to modern computing due to its straightforward implementation in digital electronic circuitry using logic gates. The simplicity of the language and its noise immunity in physical implementation make it the preferred system for almost all modern computers and computer-based devices.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a prominent German polymath from Leipzig, is credited with the modern development of the binary system in the Western world. In his article “Explication de l’Arithmétique Binaire” (published in 1703), Leibniz detailed a system that used only the characters “1” and “0”. He was inspired by the ancient Chinese text, the I Ching, which he believed showcased a form of binary calculus. As a Sinophile, Leibniz saw the hexagrams of the I Ching as evidence of binary calculus and believed that the binary numbers were symbolic of the Christian idea of creatio ex nihilo or creation out of nothing. He even associated the binary system with the Christian concept of creation, emphasizing the idea that the world was created from nothing by God’s almighty power.

However, it’s worth noting that systems related to binary numbers have appeared earlier in multiple cultures, including ancient Egypt, China, and India. For instance, the Indian scholar Pingala (c. 2nd century BC) developed a binary system for describing prosody, using short and long syllables. In China, the Daoist Bagua, dating from the 9th century BC, used a binary notation for its quaternary divination technique. The binary representations in Pingala’s system and the Daoist Bagua are precursors to the modern binary system, showcasing the universality of the concept.

Interestingly, while Leibniz’s contributions to various subjects were vast and influential, many of his works were scattered in learned journals, letters, and unpublished manuscripts. He wrote primarily in Latin and French, and occasionally in German. His binary system was indeed groundbreaking. However, it appears that he did not immediately publish his findings on binary logic. It was only after his death that his works on the binary system were discovered and recognized for their significance. This delay in publication and recognition is not uncommon for many great thinkers, as sometimes their ideas are ahead of their time or not immediately understood by their contemporaries.

The Binary System: Paving the Way for Innovations

The binary system, with its simple representation using only two elements, 0 and 1, laid the groundwork for a new era in data storage and processing. This foundational concept, introduced by Leibniz, would eventually lead to the development of the punched card in the 18th century. The punched card, a piece of stiff paper that contains digital information represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions, became a pivotal innovation in data storage and processing.

One of the earliest applications of punched cards was in the realm of music and entertainment. Barrel organs, which were popular during the 18th and 19th centuries, utilized a system of pinned barrels (an early form of the punched card) to play specific tunes. As the barrel rotated, the pins would interact with the organ’s mechanism, producing musical notes corresponding to the placement of the pins. This mechanism can be seen as an early representation of binary logic, where the presence or absence of a pin (1 or 0) determined the musical output.

Similarly, the textile industry saw a revolutionary change with the introduction of looms powered by punched cards. The most notable of these was the Jacquard loom, invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in the early 19th century. This loom used punched cards to control the weaving pattern, allowing for intricate designs to be produced with minimal manual intervention. Each card corresponded to a row of the design, and the presence or absence of a hole determined whether a particular thread would be raised or lowered. This automation not only increased efficiency but also allowed for more complex patterns to be woven, which would have been extremely time-consuming and error-prone if done manually.

In essence, the binary system’s simplicity and universality provided a logical framework that could be applied across various fields. From music to textiles, the concept of binary representation, realized through innovations like the punched card, played a crucial role in advancing technology and industry during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Financial Innovations and the Rise of Banking

The Mechanical Age, spanning from 1450 to 1840, was not just a period of technological marvels; it was a transformative era that reshaped economies, trade, and the concept of money.

The Gutenberg Press: A Catalyst for Economic Change

The Gutenberg Press, introduced in 1455, was a game-changer for the economy. It democratized information, breaking the monopoly of the literate elite and empowering the emerging middle class. This had a ripple effect on trade and commerce. The press facilitated the spread of commercial knowledge, including manuals on accounting, trade laws, and foreign languages. This newfound access to information accelerated mercantile activities and led to the rise of a business-savvy middle class.

Banking and the House of Medici

The Renaissance period saw the rise of powerful banking families, most notably the House of Medici. Their financial innovations, including the introduction of double-entry bookkeeping, were disseminated through printed books, standardizing commercial practices and boosting economic activities. The Medici family’s influence was so pervasive that they could steer economic policies, affecting trade routes and commodity prices.

Mechanical Calculators: Streamlining Commerce

Devices like Pascal’s Pascaline simplified arithmetic calculations, a boon for merchants and traders. These mechanical calculators made transactions quicker and more accurate, reducing errors in financial records. This efficiency was particularly beneficial in complex trading activities that involved multiple currencies and fluctuating exchange rates.

The Binary System: The Unsung Hero of Data Storage

The advent of the binary system and punched card storage revolutionized data handling, impacting sectors like textile and music. For instance, the Jacquard loom, controlled by punched cards, automated the weaving process, significantly reducing manual labor and production time. This automation lowered production costs, making textiles more affordable and boosting trade.

Taxation: The Engine of State Revenue

The Mechanical Age also saw the evolution of taxation systems. The printing press played a role here too, enabling the mass production of tax ledgers and legal frameworks. This standardization made tax collection more efficient, providing states with the revenue needed to invest in public works, further fueling economic growth.

In summary, the Mechanical Age was a period of profound economic transformation, driven by innovations that streamlined trade, standardized commercial practices, and modernized taxation, setting the stage for the economic systems we know today.

Electromechanical Age (1840 - 1940)

Industrial Revolution: The Information Catalyst

The Industrial Revolution, spanning from approximately 1760 to 1840, wasn’t just a shift in manufacturing and production—it was a monumental leap in the way information was exchanged, processed, and utilized. This transformative era was both a result of and a catalyst for advancements in information dissemination. Before the onset of the Industrial Revolution, information was largely localized. However, the Renaissance had set the stage by fostering a culture of inquiry and knowledge sharing. The printing press, a revolutionary invention of the 15th century, democratized access to information, allowing ideas to be disseminated on an unprecedented scale. This widespread availability of knowledge laid the groundwork for the innovations that would fuel the Industrial Revolution.

The textile industry’s mechanization wasn’t just about machines, it was about the rapid sharing and adaptation of new techniques. Innovations were no longer confined to regions; they spread across continents. As Great Britain led the charge in textile advancements, the knowledge of these techniques became coveted information, leading to industrial espionage and the global spread of mechanized textile production.

The development and perfection of the steam engine were results of cumulative knowledge. Innovators built upon the works of their predecessors, refining designs based on shared information. This iterative process of knowledge exchange accelerated the adoption of steam power in various sectors.

Advancements in iron making, especially the shift from charcoal to coke, were pivotal. But it was the exchange of this knowledge, through trade journals and international expos, that allowed these methods to be adopted globally, standardizing processes and driving down costs.

The Industrial Revolution wasn’t just about producing goods; it was about connecting markets. The ability to mass-produce and efficiently transport goods opened up new markets, creating a global economy. This globalization was not just in goods but also in information. Trade routes became information highways, leading to an era where knowledge was as valuable a commodity as the goods being traded. The rapid exchange of ideas, techniques, and innovations fueled this transformative era. It stands as a testament to the power of information in shaping the course of history.

From Telegraph to Mass Media

The telegraph, particularly the electrical telegraph, was a groundbreaking invention that dramatically transformed long-distance communication. Before its advent, messages were relayed through a series of semaphore towers or by horseback, both of which were slow and inefficient methods. The telegraph’s ability to transmit messages over vast distances in a matter of minutes or even seconds was revolutionary.

The telegraph was a significant leap in the realm of communication. Before the electrical telegraph’s widespread use, there were other forms of telegraphy, such as optical telegraphs. The earliest true telegraph was the optical telegraph invented by Claude Chappe in the late 18th century, which was extensively used in France and other European nations occupied by France during the Napoleonic era.

However, even before Chappe’s optical telegraph, there was an attempt at creating an electric telegraph system. In 1774, Georges-Louis Le Sage realized an early electric telegraph. This telegraph had a separate wire for each of the 26 letters of the alphabet, and its range was only between two rooms of his home. While this was a pioneering effort, it was not practical for broader communication needs.

The electric telegraph began to replace the optical telegraph in the mid-19th century. Samuel Morse’s system, developed in the United States, became the international standard by 1865, using a modified Morse code developed in Germany in 1848. The Morse system was more efficient and practical than Le Sage’s initial design, paving the way for the telegraph’s widespread adoption.

The telephone, introduced in 1876, further revolutionized communication. Unlike the telegraph, which required operators to translate messages into Morse code and then decode them at the other end, the telephone allowed for direct voice communication.

The radio marked another significant advancement. In 1898, the first message transmission was achieved by Ferdinand Braun over a distance of 30km. By 1920, radio broadcasting began, with test transmissions taking place in Germany and Switzerland. By 1923, regular radio operations had commenced.

The term ‘Mass Media’ first appeared in the USA in 1920, marking the dawn of an era where information could be disseminated to vast audiences simultaneously. This era witnessed the rise of newspapers, radio broadcasts, and later, television, which played pivotal roles in shaping public opinion, culture, and politics. However, with the power to influence came the potential for misuse. The mass media’s ability to reach vast audiences made it a potent tool in the hands of those seeking to manipulate public opinion.

For instance, in the early 20th century, totalitarian regimes recognized the power of mass media as a means to control and influence their populations. Propaganda became a standard tool, with state-controlled media outlets broadcasting messages that supported the regime’s ideologies and suppressed dissenting voices. The Nazi regime in Germany, for example, used radio broadcasts, films, and newspapers to propagate its messages, fostering a culture of anti-Semitism and promoting its vision of Aryan supremacy.

Furthermore, the mass media’s role in shaping public opinion also had implications in democratic societies. The ability to control the narrative and present information in a certain light could sway public opinion, sometimes leading to ‘media-driven’ panics or influencing electoral outcomes. The power of mass media was not just in informing but also in shaping how people perceived events, issues, and each other.

In essence, while the rise of mass media brought about an unprecedented era of information accessibility and dissemination, it also underscored the importance of media literacy and the need for audiences to critically engage with the content they consumed.

A New Economic Frontier

The Industrial Revolution fundamentally altered the economic landscape, not just in terms of production but also in the distribution of wealth and labor. Employment opportunities and wages increased across various sectors, making factories an appealing job option. This led to urbanization, as workers flocked to cities, which in turn improved city planning and education systems. The revolution also had a significant impact on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, marking the beginning of consistent GDP growth for the next century. Countries that capitalized on industrialization started to rely less on imports and became more self-sufficient. However, it wasn’t all positive; the rapid changes led to issues like inner-city pollution and deteriorating working conditions in factories. Governments had to implement labor and pollution regulations to ensure the safety of its people and the economy.

Financing and banking also saw a transformation. The growth demanded more capital from entrepreneurs and current business owners. Initially, financing came from merchants, aristocrats, and wealthy families. With increasing demand, general and specialist banks became more common, providing long-term loans to entrepreneurs in the revolution.

The advent of the telegraph and later, mass media, had profound economic implications. The telegraph dramatically reduced the time and cost of transmitting information, facilitating quicker decision-making in business and finance. Samuel Morse’s system became the international standard by 1865, making it easier for businesses to communicate across borders. The telephone further revolutionized communication, allowing for direct voice communication, which had its own set of economic benefits.

The term ‘Mass Media’ appeared in the USA in 1920, marking a new era where information could be disseminated to vast audiences. This had both positive and negative economic impacts. On one hand, it opened up new avenues for advertising and marketing, creating an entire industry around it. On the other hand, the power to influence public opinion also meant that mass media could be used to manipulate markets and even electoral outcomes.

In totalitarian regimes like Nazi Germany, state-controlled media outlets were used to propagate messages that supported the regime’s ideologies, demonstrating the economic value of controlling information. In democratic societies, the ability to control the narrative could sway public opinion, sometimes leading to ‘media-driven’ panics that could affect market behavior.

In summary, the electromechanical age from 1840 to 1940 had a profound impact on economics, trade, and money. It transformed the way goods were produced, how information was communicated, and even how capital was generated and allocated, laying the foundations for the modern economic systems we have today.

Electronic Age from 1940 Onwards

Rise of Computers

The 20th century marked a significant shift in the realm of computing, transitioning from mechanical aids to electronic marvels. This evolution not only transformed the way we processed and stored information but also how we disseminated it.

1st Generation (1940s)

The dawn of the electronic age in computing began with the first programmable binary calculating machine in 1941, developed by Konrad Zuse. This era was characterized by the use of vacuum tubes and magnetic drums for data storage. The machines were massive, consumed a lot of power, and were prone to frequent breakdowns. However, they marked the beginning of a new age in computing.

2nd Generation (1950s-1960s)

The second generation saw the replacement of vacuum tubes with transistors, making computers smaller, faster, cheaper, and more energy-efficient. This era also witnessed the replacement of punched cards with magnetic tapes for data storage. A significant development during this period was the introduction of the programming language FORTRAN, which revolutionized the world of computing by allowing humans to communicate more easily with machines.

3rd Generation (1960s-1970s)

The third generation brought about another significant shift with the replacement of transistors by integrated circuits and chips. This miniaturization allowed for even more powerful and compact machines. The emergence of operating systems became prominent during this period, simplifying the user-computer interaction. Moreover, the programming language BASIC was introduced, further democratizing the world of computing.

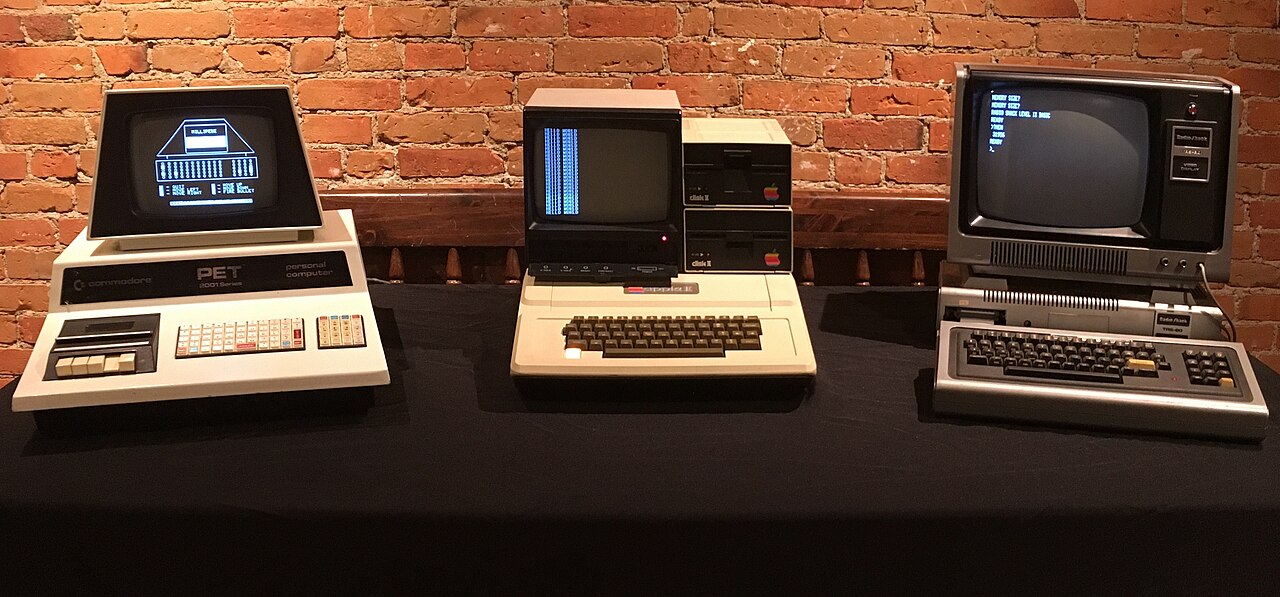

4th Generation (1970s-Present)

The fourth generation witnessed the birth of CPUs and the personal computer. Apple II, introduced in the late 1970s, became one of the first successful consumer devices, marking a significant milestone in making computing accessible to the masses. This era also saw the introduction of the first Graphical User Interface (GUI), which transformed the way users interacted with computers, making them more user-friendly and intuitive.

The digital age, characterized by the rise of computers, has had profound implications on society. From communication and work to entertainment and leisure, electronic devices have become an integral part of our daily lives. The rapid advancements in computing technology have not only made information processing more efficient but have also democratized the access and dissemination of information, reshaping the contours of the modern world.

The Internet: Connecting the World

The digital revolution, marked by the rise of the internet, has been a transformative force, reshaping the way we communicate, work, and live. The early phases of the internet can be traced back to the 1960s when the foundational technical basics were laid. Initially, the internet was a project driven by military needs. However, by the 1970s, its potential for academic research became evident, leading to a shift from military to academic applications.

The internet’s commercial phase began in the 90s, marking a significant turning point in its evolution. This period saw the internet transition from a tool for researchers and academics to a global platform accessible to the general public. The impact of this transition was profound, influencing globalization, commerce, and the accessibility of information. The internet’s role in modern warfare also evolved, with cyber threats emerging as a new domain of conflict.

One of the earliest forms of the internet was based on packet switching, a concept developed independently by Paul Baran at the RAND Corporation and Donald Davies at the National Physical Laboratory in the UK. This technology allowed data to be broken into packets and transmitted across a network, revolutionizing data communication.

The ARPANET, developed in the late 1960s, adopted this packet switching technology and laid the groundwork for the modern internet. This network was a project of the United States Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). By the late 1970s, various standards and protocols for internetworking emerged, enabling different networks to be interconnected, creating a “network of networks.”

The 1980s and 1990s saw rapid advancements in digital technologies. Email became a new form of communication, allowing instant messaging across vast distances. The rise of platforms and social media provided people with new ways to connect, share, and communicate. The emergence of cryptocurrencies introduced a novel form of digital currency, while memes became a cultural phenomenon, reflecting societal trends and sentiments. The development of learning algorithms and machine learning paved the way for smarter, more efficient systems. Virtual worlds, too, began to take shape, offering immersive digital experiences.

The Digital Economy: A New Frontier

The electronic age, particularly the rise of computers and the internet, has had an indelible impact on the global economy. The shift from mechanical to electronic computing has not only revolutionized information processing but has also created a new economic sector: the digital economy. This economy is characterized by the use of digital computing technologies in business, education, government, and other societal activities.

The first generation of computers, despite their limitations, laid the foundation for computational finance and data analysis, which would later become integral to economic planning and forecasting. The advent of transistors made computers more affordable and reliable, leading to their adoption in business operations, thereby increasing efficiency and reducing costs. The introduction of FORTRAN enabled complex calculations that benefited sectors like engineering and economics. Integrated circuits further miniaturized computers and made them accessible to smaller businesses. This democratization of technology led to the rise of the software industry, creating new jobs and contributing significantly to GDP. The personal computer and the internet have perhaps had the most profound economic impact. They have democratized information access and created a plethora of new industries like e-commerce, digital marketing, and IT services.

The rise of the internet has been a catalyst for globalization, enabling businesses to reach international markets with ease. E-commerce giants like Amazon and Alibaba are prime examples of how the internet can be leveraged for massive economic gain. The internet has also democratized content creation, allowing anyone to be a producer and find an audience, thereby challenging traditional mass media models. The digital age has also given rise to the data economy. Companies now leverage data for targeted advertising, market research, and customer service improvement. This has led to the emergence of big data analytics as a field, creating new job opportunities and contributing to economic growth. Digital payments, including cryptocurrencies, have not only made transactions more convenient but have also brought financial services to previously underserved populations. However, this shift towards a cashless society has raised concerns about financial inclusion and privacy.

While the digital revolution has brought about significant economic benefits, it also poses challenges such as job displacement due to automation and the ethical considerations surrounding data privacy. Regulatory frameworks are being considered to ensure that the digital economy is inclusive and sustainable. In summary, the economic impact of the electronic age is multifaceted, affecting various sectors from finance and retail to media and education. As we continue to innovate, the economic landscape will undoubtedly continue to evolve, offering both new opportunities and challenges.

Conclusion

Throughout human history, the ways in which we communicate, store, and disseminate information have undergone remarkable transformations. From the rudimentary symbols on cave walls to the vast cyberspace of the digital era, these shifts, often termed “information revolutions,” have redefined the paradigms of societal interactions and knowledge dissemination. These revolutions encompass both the symbolic systems, such as the alphabet or binary code, and the mediums, like papyrus, the printing press, or digital storage, which carry these symbols.

Understanding the nuances of these information revolutions is more than a mere academic endeavor. It offers a unique perspective on the broader trajectory of human advancement. These pivotal shifts in information mediums and methods have left an indelible mark on various facets of civilization, including governance, commerce, cultural evolution, and interpersonal dynamics. For instance, the transformation of writing systems, from rudimentary pictograms to comprehensive alphabets, didn’t just streamline communication. It enabled civilizations like Egypt and Greece to record history, myths, and a plethora of knowledge. Similarly, the emergence of writing systems like cuneiform had transformative economic repercussions, fostering transparency and organization in ancient trade practices.

Recurring Patterns

A recurring theme in the annals of information revolutions is the relentless quest for efficiency and clarity in communication. The Phoenician alphabet, for instance, streamlined communication, while Greek innovations added vowels to enhance clarity in linguistic expressions. Another persistent pattern is the impact of these revolutions on the broader socio-economic landscape. The development of systems like the Hindu–Arabic numerals didn’t just revolutionize numerical representation; they influenced diverse realms from trade to academia.

Challenges and innovations have always been intertwined in the course of these revolutions. As societies evolved, so did their communication challenges, leading to the birth of new mediums and systems. The patterns seen in history—from the advent of the abacus to the telegraph—hint at a constant: the intertwining of human needs and technological advancements, creating a cyclical pattern of challenge, innovation, and adaptation.

Technological Surprises

The history of information revolutions is replete with unexpected advancements. One such instance is the synergistic relationship between new mediums and systems. The emergence of the printing press, for example, catalyzed the widespread adoption of the Latin alphabet. Similarly, the birth of the internet led to the creation of innovative coding languages. In our contemporary era, the rise of artificial intelligence and chatbots stands as a testament to this legacy of unforeseen technological leaps. These AI-driven tools, initially perceived as mere digital assistants, are now reshaping the landscape of communication, knowledge dissemination, and even creative endeavors.

The Road Ahead: Embracing Change

The myriad information revolutions that dot our history serve as not just milestones of past achievements, but as beacons for the future. By internalizing the lessons from these shifts, we garner insights into the fluid dynamics of power, knowledge dissemination, and human connectivity. Such understanding is more than a retrospective exercise. It’s an imperative, guiding us to adeptly navigate the present and to aptly prepare for what lies ahead. As we stand at the cusp of yet another information revolution, marked by AI and quantum computing, our collective resilience, adaptability, and foresight will determine not just our survival but our thriving in the face of change.

References

-

Abbate, J. (2000). Inventing the Internet. MIT Press.

-

Babbage, C. (1989). Passages from the Life of a Philosopher. Rutgers University Press.

-

Baran, P. (1964). On Distributed Communications: Introduction to Distributed Communications Networks. RAND Corporation.

-

Bruce, R. V. (2007). Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude. Cornell University Press.

-

Carey, J. W. (1989). Communication as culture: Essays on media and society. Unwin Hyman.

-

Campbell-Kelly, M., & Aspray, W. (1996). Computer: A history of the information machine. Basic Books.

-

Charpin, D. (2010). Reading and Writing in Babylon. Harvard University Press.

-

Cortada, J. W. (2004). Before the Computer: IBM, NCR, Burroughs, & Remington Rand & the Industry They Created, 1865-1956. Princeton University Press.

-

Crook, T. (1990). Radio drama: Theory and practice. Routledge.

-

Eisenstein, E. L. (1983). The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

-

Gleick, J. (2011). The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. Vintage.

-

Hankins, T. L., & Silverman, R. J. (1995). Instruments and the Imagination. Princeton University Press.

-

Hale, T. A. (1998). Griots and griottes: Masters of words and music. Indiana University Press.

-

Heide, M., & Storsul, T. (2018). Understanding media displacement: An innovation perspective. Media International Australia, 169(1), 33-45.

-

Houston, S. D. (2004). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press.

-

Hobsbawm, E. J. (1962). The Age of Revolution: 1789-1848. Vintage.

-

Hu, D. (1985). A Brief History of Chinese Mathematics. Springer.

-

Lasswell, H. D., & Lerner, D. (1952). The policy sciences: Recent developments in scope and method. Stanford University Press.

-

Man, J. (2002). Gutenberg: How One Man Remade the World with Words. John Wiley & Sons.

-

Mayer-Schönberger, V., & Cukier, K. (2013). Big data: A revolution that will transform how we live, work, and think. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

-

McNeill, W. H. (1990). The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community. University of Chicago Press.

-

Needham, J. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press.

-

Rifkin, J. (2014). The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism. St. Martin’s Griffin.

-

Schramm, W. (1963). Mass media and national development: The role of information in the developing countries. Stanford University Press.

-

Standage, T. (1998). The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s On-line Pioneers. Walker & Company.

-

Tallet, P. (2012). “The Red Sea in Pharaonic Times: Recent Discoveries Along the Red Sea Coast.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 42, 389-401.

-

Tapscott, D., & Williams, A. D. (2008). Wikinomics: How mass collaboration changes everything. Penguin.

-

Usher, A. P. (1929). A History of Mechanical Inventions. Harvard University Press.